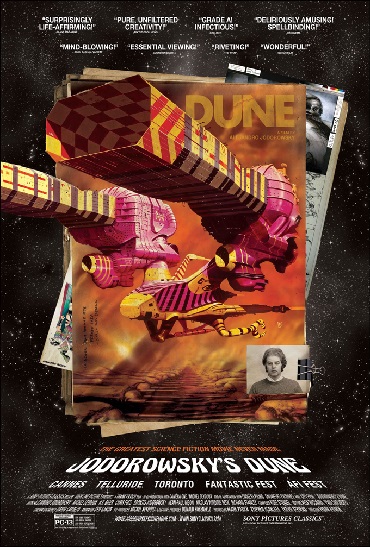

Jodorowsky's Dune (2014)

Posted on August 11, 2014 by Mike Granby

Jodorowsky's Dune tells of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s fabled attempt to bring Frank Herbert’s masterpiece to the screen. Fascinating stuff, with the 84 year-old Jodorowsky regaling us with his ambition to create a “spiritual” movie to “change the consciousness of the young people” (yes, I know) after his frankly bizarre El Topo and The Holy Mountain. Encouraged by his French producer, he pulled Dune out of the air as an idea for a movie he’d like to make, not having read the book but having had it recommended by a friend. Not an auspicious start, but one in keeping with the man whose study, as we see during the opening sequence, seems to be decorated with an awful lot of pictures of himself.

Anyway, having read the book and appreciated its qualities, he sets off on a bizarre adventure to assemble his team of “spiritual warriors”. Having first approached Douglas Trumbull of Space Odyssey fame to handle the special effects, and then having rejected the “unspiritual” 2001 designer, he stumbles on to Dan O’Bannon after seeing his work on Dark Star. He recruits sci-fi cover artist Chris Foss and French comic book artist Moebius, and even adds HR Giger to his crew, getting him to work on designs for the Harkonnen castle. Two things strike you about Giger from his segments: First, he has an incredibly creaky and creepy voice, almost Dalek like, and entirely suitable for a mind that has produced such disturbing images. And second, so many of the materials you see developed for Dune end up being used in later in movies like Alien and Prometheus. The documentary cites this as an example of the project’s impact, bringing together as it did O’Bannon and Giger who would later script and design Alien, but I have to say that it is also a reflection of the fact that Giger has basically been drawing the same designs for the best part of his career!

The film tells of Jodorowsky’s attempt to recruit his cast. We hear about David Caradine, improbably downing a $60 container of Vitamin E in one go. We hear about Salvador Dali and his muse Amanda, whom he respectively wanted to play Shaddam and, as a sop to Dali, Irulan. We hear about Orson Welles, whom he claims to have bribed into playing the Baron by offering to have his favorite French chef cook meals for him on set. And we hear about how Mick Jagger strode across a huge room at a party to stand silently in front of Jodorowsky only to reply with the single word “Yes” and then leave when the director asked him from nowhere if he’d like to play Feyd. There is, as befits Jodorowsky, a surreal air to these stories, and frankly there is a distinct Munchhausen feel to the whole thing as well, as if these are tales that grow longer with each telling. The casting of his son as Paul also further illuminates the director’s outsized ego, and his hiring of a martial arts instructor to teach the then 12 year-old six hours a day for two whole years makes one wonder as to whether Jodorowsky’s smiling, charming persona is quite the whole story.

The project ends in failure – but not entirely. It gives birth to a huge bound presentation of the concept – a book, I’d guess 18” by 12” in size and at least 6” thick, containing drawings of the characters and the sets, and storyboards of the whole production, shot by shot. The book was sent to every major studio in Hollywood, all of whom praised its execution but balked at handing over the $15m in 1970’s funds that were needed to complete the production, especially with a character like Jodorowsky at the helm. The studios also complained about running time. They wanted 90 minutes (ridiculously short for such a complex story, as shown later by Lynch’s own attempt) but Jodorowsky wanted something much more ambitious. The documentary doesn’t say exactly how long he demanded – the director talks of his right to have 12 or 20 hours for his vision if that’s what he needs – but one wonders whether that lack of perspective didn’t help undermine his case as much as his unstable reputation.

In one scene when discussing the rejection of his movie, Jodorowsky’s rage comes across as he decries the money men who run Hollywood and how money controls our society and our lives. It’s a facile complaint, I feel, often made by those who define money as so unimportant that they want other people to give them lots of it so they can continue to have their own wishes fulfilled. (One wonders who was funding Jodorowsky’s adventures in chasing Welles, for example, allowing him to send the most expensive wine in the restaurant to his table.) And we also hear of his joy at seeing Lynch’s version, which he, and many others, considered a failure. A human reaction, he admits, reminding me of Gore Vidal’s acidic comment (I think it was him – it certainly fits his style, but I wrote this with no Internet for fact checking so forgive me if this or any other items turn out to be inaccurate) that it it was not enough for him to succeed, but rather that he also needed to see others fail.

But anyway, the movie didn’t happen, and most of the work ended up in comic books that Jodorowsky developed with Moebius and others. The team he assembled, though, was special. Almost a cult, driven by a frankly rather questionable man who contradictorily talked of the importance of individual vision while also demanding that every scene, every design “match his dream”, they went on to much greater things. Even the magnificent storyboard had its impact. There’s a little montage showing how Lucas might have been “inspired” by its sword fighting and training sequences – a credible claim, given the opinion I’ve latterly formed of the man. So, while the assertion that without Jodorowsky’s Dune the “world would not have been the same” is a little too strong, it certainly contributed a lot more than you’d expect for a movie that never was.

back